About a month ago I saw Penny Neff on gchat and we had the following conversation:

About a month ago I saw Penny Neff on gchat and we had the following conversation:

me: hi! are you lost?

penny: haha, why?

me: i've never seen you here! [on gchat] also, i forget where you are

penny: well, now i'm back in jersey, at my mom's house. i was in nigeria, working on a short-term project for an NGO, but i was in a car accident so now i'm back home recovering

me: oh no. what happened?

penny: i was in a head on collision and broke my back

I had to google "broken back" just to stay in the conversation.

Last I had heard, Penny was teaching at an environmental school in the Bahamas, with an unbroken back, so I was surprised by about 100% of that conversation. I had met Penny in biology class during our senior year at NYU, and after I convinced her to start coming to Earth Matters! meetings we became pretty friendly. As someone perpetually considering moving to Africa and doing NGOish work myself, her situation and story resonated with me quite a bit. And thus, about a week after visiting Penny at her mom's house in Teaneck, NJ, I asked her if she'd tell me about the accident.

So you were in Nigeria.

That's a good place to start. I went with an NGO, OIC International, based out of Philly and I got there around July 15th. I was a "medicinal plant specialist" - I had studied bush medicine in the Bahamas. The "specialist" part actually made for some awkwardly hilarious moments when people thought I could tell them all about their plants in Africa, and I had to explain that expert was a bit of a stretch. I got introduced as a plant doctor at a village's micro business training and everyone went crazy.

What were you supposed to be doing there?

My project was to be three weeks long, but the actual project changed several times, Originally I thought I was going to be working with a women's co-op that wanted to grow medicinal plants for sale, and I was to assess who they could sell them to, what plants would be most interesting to outsiders, etc.

But then I found out I was supposed to work with a school in the same town, planning a botanic garden. However, the morning I was supposed to start - I had met with my host family and everything - we got a call that they had been robbed the night before and my project manager didn't think it would be safe for me to go there. You also have to understand, I was going to be in a village with no electricity or phones, where even cell phones didn't work, so if something went wrong I would have no way of doing anything about it. We visited the village and it was beautiful, but more middle of nowhere than I'd ever seen before.

Did all of that make you nervous?

Not really. The weird thing is that for some reason I had a feeling something would go wrong from the beginning. Maybe just because the NGO seemed disorganized, but when I told people I would see them later, I thought in the back of my head "as long as everything works out". But I wasn't necessarily nervous, just prepared for something to go wrong.

How were your first few days?

Well, the first 2 days were totally disorganized because I didn't know what I'd be doing or where I'd be doing it. I was eventually reassigned to a village called Alok, and I moved into a hotel room in Ikom, a bigger "city".

Alok has these amazing stone monoliths carved 2-3 thousand years ago, and the Cross-River State Tourism Bureau, among others, is working on an outdoor museum. In the south eastern part of Nigeria, near Cameroon. I was going to be working with an American girl, April, interviewing the local oral historian about medicinal plants near the monoliths, to collect information for tourism literature and signs for the museum as well as perhaps plans for villagers to market medicines to tourists.

The third day, I was in the forest villages, seeing drill monkeys,which were assumed to be extinct and are now being captive-bred for reintroduction into the wild. Then we got a late start back to the hotel - that was when I got introduced as a medicine doctor and there was a lot of hubbub. Seven of us were piled into a pickup truck: me, April, Kennedy (an OIC director), Patricia (another volunteer like me), two other volunteers and our driver Charles. Charles, April and I were in front, buckled up, and everyone else in the back wasn't wearing a seat belt, as far as I know. Also, it was dark outside, and because it's the rainy seasons there now, it was raining.

Right before the accident, I remember thinking that we were going too fast and I wanted to say something to Charles, but safety is really different down there and I’m sure he wanted to get home. I would say we were going about 40 mph, maybe faster. As we're going around a bend, a car coming at us starts swerving. At first I thought they were OK, just took the curve a bit too quickly, but then they were coming right at us. For a while afterwards I kept seeing the car coming at us and the cracked windshield with light shining through. I remember thinking right before we collided, "oh shit, this is going to be bad. There are no hospitals anywhere." It happened very quickly and I don’t think either car tried to slow down before the collision.

The other car was in your lane?

I think so. I couldn't see any of it after the fact because I couldn't move. The police determined that it was the other car's fault, whatever good that does.

I remember opening my eyes after the impact, and I had hit my head on the dashboard and immediately became conscious of terrible pain in my lower back and abdomen. I felt as if my torso was being strangled by the seat belt. I opened the door and tried to take off my seat belt to stop the pain, but I remember that the back of my seat had collapsed and it was difficult to get to the seat belt release. April was sitting next to me and tried to help me out of the seat belt, but I got tangled and fell out the car door. Then I just laid on the side of the road next to the car, not knowing what to do. The whole time it was pouring rain. April was freaking out because she had hit her head and was covered in blood.

What was your first thought?

Immediately I was thinking, shit, back injuries are BAD. After the accident, I was carried out of the rain to a shelter off the road (I believe by people in the village where the accident occurred) and I was then put in the back seat of a car to be driven to a hospital in Ikom. My back felt like it was collapsing and of course no one knew how to carry someone with a spinal injury and I must have sounded like a nut, screaming instructions to everyone. I'm not sure anyone could understand what I was saying, which was mostly just, "Support my lower back!" Also I was freezing and I really wanted someones coat. I was shaking uncontrollably, but mostly I wasn't able to talk much at the time. The pain was so intense, I have never felt anything like that before and I didn't feel like I could make sense or think properly or anything.

How were the other people in your car?

Patricia, one of the other volunteers, was injured pretty seriously and got put in another car and taken to a different hospital The others were scraped and bruised and in a ton of pain, but up and moving around.

Then you went to the hospital?

The hospital was in Ikom, which was about an hour from the accident. The doctor at the hospital wasn't there right away, so I laid in bed by myself for a while. At some point the doctor came back and I got an IV and was given some pain killers, but the doctor didn't do much else, not even look at my back or take my pulse or blood pressure. I ended up checking my own pulse because I was freaked out no one else did it, and it didn't sound too fast so I decided I'd probably be OK. I was in the women's ward, with at least 5-10 other women that moaned and coughed all through the night.

At 6 in the morning a preacher came in to get everyone up with some inspirational talks about God. And, of course, the doctor left for the night with no instructions to give me more pain medicine, so I woke up around 1-2am in terrible pain. I felt like such a pathetic American, wanting medicine while everyone else suffered. The people generally spoke English, but that doesn't mean it's easy to understand for an American...the accent was totally nuts for me. And beyond the language, our expectations are so different in a hospital that I felt like often I couldn't communicate with people.

Did you talk to the other patients at all?

No, I couldn't move and no one was right next to me. The next day some of them came up to me to say they were sorry. (That's what everyone who visited me did: apologize. I still can't figure out what it meant, exactly) I spent most of the night just writhing and calling for the nurse.

What was your mental state like?

Shit shit shit shit. There's nothing to focus on but the pain. in some ways it was a very stable mindset. It makes me understand why people with chronic pain sort of lose themselves. This might sound all dark and creepy, but I really thought that if it continued hurting this much there was no use in living. Which is way too dramatic since I wasn't dying, but I just didn't know how to handle it. And at the time, I was terrified of having internal bleeding, since I knew I wouldn't get help in time for that, It's hard to explain how difficult it is to know what's going on when all you can look at is the ceiling or sky.

Were you in touch with the other people from your car?

Kennedy was with me. April came to visit the next morning, I think - it's all sort of fuzzy. I was told that Patricia, the other American volunteer, was at a different hospital but that she was OK. I think everyone but Patricia visited me the next day.

Kennedy told me that they were arranging for an ambulance to take us all to a better hospital in Calabar the next morning, but we didn't leave until after 4pm, so we had to drive at night again, which totally freaked me out. The goal in Calabar was to get x-rays and hopefully more consistent pain relief

Were you thinking to yourself, I'm keeping it together pretty well, or that you were going crazy, or were you not even thinking about kind of stuff?

I wasn't thinking about it at all, really. When I was on painkillers I tried to keep it together, especially since everyone I'd ever met in the area visited me that first day in the hospital and I wanted to be grateful and not a raving lunatic. But it was driving me crazy that everyone kept saying they were sorry, or that I would be fine, or that God was watching over me, but no one except April would just talk about it like it was. That's the American thing. I just wanted to talk about the reality of what I could be facing. Same with her, since she had a pretty fucked up forehead, lots of glass and all

How was the new hospital?

I was just wishing wishing wishing that I'll be greeted by EMTs who know how to carry people and work a stretcher (no one knew that the stretcher in the ambulance could come out and roll, I think it was the first time the ambulance was used). So we get to the hospital and there is a nurse and doctor but no one who knew how to work a stretcher and I had to explain about taking it out of the ambulance, and then of course the clinic was not set up to accommodate things like that--all stairs and small hallways and tight turns.

Overall the new hospital was much nicer, but they still didn't give me consistent pain medication, so I was a roller coaster of pain and then sanity and then pain again. There was actually a really interesting article in the NY Times about this, the lack of pain medication in developing countries.

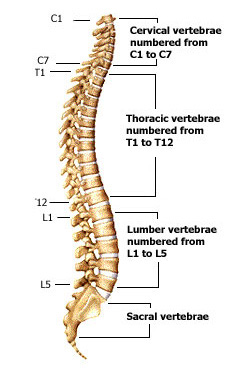

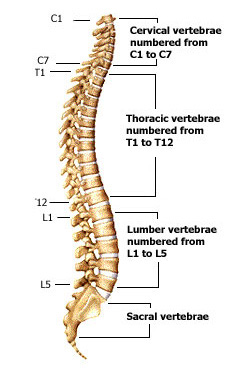

I got an x-ray the next day, 3 days after the accident by now. First day I had a full meal, too, but I couldn't really eat because everything hurt so much. The x-rays showed that I had several fractures in the lowest vertebrae, L4 and L5. The orthopedist said they were potentially unstable, as in, possibly going to cause or already caused nerve damage. I was fitted with a traveling fiberglass torso cast and from then on was treated as a spinally injured patient, which means special ways to turn me on my side and move me, etc.

I got an x-ray the next day, 3 days after the accident by now. First day I had a full meal, too, but I couldn't really eat because everything hurt so much. The x-rays showed that I had several fractures in the lowest vertebrae, L4 and L5. The orthopedist said they were potentially unstable, as in, possibly going to cause or already caused nerve damage. I was fitted with a traveling fiberglass torso cast and from then on was treated as a spinally injured patient, which means special ways to turn me on my side and move me, etc.

Did the doctors have a prognosis for you, aside from maybe nerve damage?

They just wanted to get me to a better hospital where I could get an MRI, so this whole time my air evacuation was trying to be sorted out. The NGO fucked up and their insurance wouldn't cover it, but luckily I still had my global insurance from my work in the Bahamas. So it was decided I was going to be flown to Paris.

Can you explain the insurance issue?

The insurance was a complete mess the whole time I was there. Essentially, they found out after all this that their insurance only covered local evacuations. Another woman, Patricia, was also in bad shape and it was going to cost $90,000 to get us both to a better hospital in Europe or the US. They didn't find anything in her x-rays, but it ended up that she had I think 3 pelvis fractures that are hard to see in x-rays but easy with CT scans. So she ended up being flown home on a normal flight, in coach, and it was terrible.

When they found out about their insurance - they told you as a sort of "well, this happened but we will take care of it", or as in "well this happened and we don't know what to do now?"

"We'll take care of it," but it didn't seem like anyone really knew what to do and I was pretty nervous. They couldn't pay for it without approval from the board--anything over $30,000 needed approval. I also didn't have a cell phone so I could only hear about things from the American side when I talked to my dad once a day. There's a whole inquiry thing going on right now, and they changed their insurance right away. So finally it became clear that the fastest thing was to get me out with my personal insurance, not their travel insurance. The whole insurance thing was stressful...the hopelessness of the situation felt terrible, I felt like I was never going to know what was wrong with me and get help.

Anyway, I was picked up 6 days after the accident by a little jet to fly to Paris.

How was the Paris hospital?

Paris was a bit less eventful, just good health care. I was very excited when the nutritionist came to see what I wanted to eat and said that there were 22 varieties of cheese. They said I had no neurological damage, although apparently I was close.

What did they say about your recovery?

Well, that I'd have to be in my super crazy corset for 3 months, that I'd probably be fine but was at risk for arthritis and back pain my whole life. But that I would be able to have children, be normal, etc.

How long were you there?

About 10 days in Paris. At some point we should talk about the other people, really.

OK. The people from the other car?

Yeah. There were 8 people in the other car, which was a sort of taxi, taking a bunch of people who were all going towards the same place.

Only 2 survived, a mother and her son. I don't know much more than that. The woman got out of the hospital rather recently; she was apparently at the same hospital as me, but in a different room so I never saw her. I haven't quite figured out how to handle the fact that other people died, and it was probably mainly because we were in a truck and they were in a small car. April saw them and said that it didn't look bloody, but I think 2 or 3 people were dead on impact. I was sent pictures of the cars after the accident, and the little car essentially has no engine left, the entire front is gone. I’m not sure how they even got people out of the car.

Were they all Nigerian?

Yeah, from different villages I think. I’m hoping to send my leftover money back to the woman who survived. You know, we never knew much about the other people, since no one knew them, they were just passing through. I know that one of them was traveling with 90,000 naira (about maybe $700 or something) and the villagers collected everyone's belongings and returned it to the deceased's families and the villagers apparently took care of the woman's child until she was conscious.

It was a classic clash of privilege, you know? We were in a new Hilux truck, some of us wearing seat belts, expecting good health care and then the other car was so small and I doubt anyone was wearing seat belts if there were 8 of them in it, and they essentially had no chance. The woman who survived stayed in that first hospital, I think. I’m not sure what they were able to do for her, really.

I mean, there were chickens running under my bed in the morning. It just wasn't what a Westerner would accept in terms of health care. I felt totally conflicted because I wanted my nice safe health care, even though I knew it was unavailable to so many people and that I was coming from such a privileged place.

Health care or any sort of social capital in developing countries is at such a premium. "Brain drain" - probably about half of all Nigerian doctors leave the country as soon as they can.

I know. Apparently at Patricia's hospital, at the very beginning, the doctor was great, probably trained in Europe, but had no supplies to work with. And my orthopedist was wonderful, but he couldn't do anything but send me elsewhere. The nurses all said to me, well, now childbirth won't be hard for you at all

Do you see any connection, irony or...fittingness or god damn-ness about going there to study a sort of indigenous very natural kind of medicine, and then the aftermath?

Haha, yes, it was fairly fitting. I really respect just basic medical care and think that we Westerners are very lucky in some ways, but we have come to assume that our health care is normal and death and pain are not, and its just not like that in other places. And hey, morphine is from opium. Yay plants.

Now you've been home for month, month and a half? How has it been?

Now you've been home for month, month and a half? How has it been?

Yeah, probably 6 weeks I think I was a lot better off before I came home in someways, because I was just focused on survival and not; really emotional and not thinking about the future, except for one conversation with my physical therapist about what my life could be like. Then...I'm living in my mom's living room. unable to walk, really. can't shower, can't eat sitting up, and I’m like, shit. I’m a cripple. This is terrible. Of course, I got better quickly, but there's something OK about being unable to take care of yourself when you're in a hospital with nurses who are paid to do it. It's very different when you're back in your mom's house at 24.

When you got to Paris, did they take off the Nigerian fiberglass cast?

Yeah, and fitted me with the fabulous corset that you witnessed. I wanted to take my Nigerian cast with me because everyone had signed it, but it was too big. My new French corset was hard plastic and went from up by my collar bone down to my lower back/butt. It was black with straps and a hole for my breasts, which made me feel like a mix between Batgirl and a 19th century porn star.

I've now got a 3rd brace, that's a bit lighter weight and made from cloth and foam. The 3rd one makes me feel very medical. It's white with a lot of strings and metal clasps and velcro - but it breathes more.

What have the doctors been saying lately?

It seems like I'm healing super fast - I thought I was going to have to be in the French corset for much longer, about 3 months, and he said I should move on to the new back brace after only 2 months. I saw the latest x-ray and my main bad fracture just looked so much nicer and smaller. I should be able to start physical therapy in a few weeks, which to me is really when I start to begin that next step in the healing process. Even though I can lead a more "normal" life now, I am still reminded often that I am weak and my body is not responding to things as it used to. I think most of that is now muscle weakness, and I can't wait to be able to stretch and exercise and restrengthen my back. It's very funny, I used to hate exercising and now the thought of it is really comforting.

If OIC offered you another job in Nigeria, would you go back?

Oh, that's a really great question. I think there's two parts to that: was the work I was going to do really that useful? And, am I too scared to go back?

For the first part: Because of the accident, I've been focusing on the medical system in Nigeria, its lack of resources, etc. However, we did not talk about the actual usefulness of the work I was to do in Nigeria, or in general the benefit of US development aid as it is now. I'm not sure how much development work needs to be done by Americans traveling to Africa, instead of by the affected people themselves. Which would be more positive locally, as well as save money that could instead go to local people--I mean, several thousand dollars was spent to send me to Nigeria. Our funding required my airline tickets to be on an American airline, but was that the best option? I don't know too much about it, but it seems that a lot of US money goes to helping Americans, who in turn "help" Africa--a good example is selling cheap US commodities to NGOs in Africa, who then sell the US commodities at low prices to make money for the organizations. All this at the expense of and instead of buying from African farmers or African manufacturers. I'll plug another good NYTimes article.

The NGO I was working for is not involved in anything like that, as far as I know, but I do think that sometimes our aid is not really as useful as we think or hope it is. My experience in this area is extremely limited, but I want to learn more about it. I'm also not sure what other possibilities are out there--it seems like funding requirements can really limit options. At the same time, it was such an amazing and exciting opportunity for me, personally, that it's hard not to be grateful and hope for that sort of thing to pop up again.

As for the second part: when I was in Nigeria in my various hospitals, everyone kept asking me if I would come back and saying they hoped I would. I mean, the freaking governor visited me in the clinic. This was clearly partly a tourism/funding thing, as well as I'm sure genuine concern that I wouldn't come back to their country. And I would think, hell no, I just want to get home where there are traffic laws and emergency rooms. Then, once I got back, I wondered about my project and how it was going and how much I personally regretted not being able to really talk to the local oral historian and medicine expert, and I felt like if I could, I would want to go back and finish my project, although I think by the time I can travel comfortably my role may already be over (or I may need to make some real money). Now, I feel like in some ways I was intimately involved in how things go in Nigeria and really experienced what it is like to leave your expectations back where you come from (even though I was treated to the best there was). I met so many great people while I was there and so quickly understood how cultural and historical and economic differences affect everything and I feel sort of humbled.

No comments:

Post a Comment